The 100 Year Compromise

How Black History Was Boxed, Branded, and Contained and What the Next Century Demands

The Desk

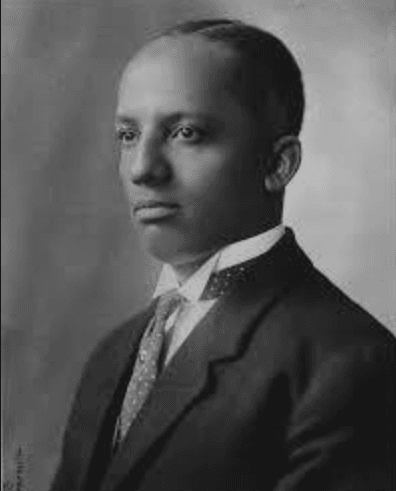

In the winter of 1926, Carter G. Woodson sat at a wooden desk illuminated by lamplight, its surface crowded with pamphlets, lesson guides, handwritten correspondence, and drafts addressed to teachers, churches, and Black civic organizations across the country. Ink stained his fingers from hours of writing. The room carried the familiar scent of paper, oil, and age. Woodson was not attempting to create a celebration or a ceremonial observance. He was responding to what he understood as a structural emergency. American classrooms were producing generations of students who could recite the nation’s story with confidence while remaining largely unaware that Black people had shaped its foundations.

Negro History Week was conceived as a corrective instrument, not an endpoint. Woodson intended it as a lever, a forced insertion into an educational system that had already decided whose experiences constituted American history and whose were to be treated as peripheral. February was selected not for its brevity, but for its strategic resonance, anchored within Black community commemorations of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Black Americans were already remembering themselves. The nation was not. One hundred years later, the intervention still exists. What has changed is not its visibility, but its function.

From Wedge to Wall

Negro History Week achieved its immediate objective. It spread across schools and civic institutions, generated teaching materials, and made outright omission increasingly difficult to defend. Over time, the observance expanded, first informally and later through federal recognition. In 1976, amid the symbolism of the United States Bicentennial, Black History Month was officially acknowledged at the national level and widely received as a gesture of inclusion. It felt like progress, and in important ways it was. Yet the expansion of the calendar never translated into a restructuring of the curriculum itself. The symbolic gesture replaced the systemic correction Woodson had envisioned. The calendar changed, but the narrative remained largely intact.

What had been designed as leverage gradually hardened into containment. Institutions discovered that a single month could absorb public pressure without requiring a reorganization of the story told during the remaining eleven months of the academic year. Celebration proved far less disruptive than integration, and the compromise settled quietly into place.

Included vs Integrated

The centennial compels a distinction that has long gone unnamed. Inclusion and integration are not interchangeable, and the failure to differentiate between them explains why the same debates recur across generations. Inclusion allows for chapters, sidebars, notable figures, and commemorative programming. Integration requires the narrative itself to be reorganized because the truth demands it. An integrated history cannot treat Black people as episodic participants who appear only during moments of national crisis. It must acknowledge Black Americans as continuous actors whose labor, intellect, resistance, and creativity shaped the economy, political institutions, culture, and moral vocabulary of the nation across every era. Most American textbooks opt for inclusion because integration would require relinquishing control over the default story of American development.

The Sprinkle Strategy

The pattern embedded in American textbooks is consistent and revealing. Black history appears prominently during discussions of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights Movement, then largely recedes from view. This is not the result of missing information. It is a narrative discipline that preserves a particular vision of American history as neutral and universal, while relegating Black experiences to specialized moments of disruption. Scholars of curriculum and textbook history have documented how mainstream texts routinely soften conflict, avoid naming white supremacy as a causal force, and frame racism as an unfortunate deviation rather than an organizing principle. When indexes barely reference racism, the book is signaling what it considers foundational and what it considers incidental. The result is an education that trains students to see Black Americans primarily as subjects of suffering or protest, rather than as architects of systems, institutions, and ideas. Black presence becomes conditional, appearing when the nation requires moral reckoning and receding once it has reassured itself of progress.

When the System Reveals Itself

At moments, the mechanics of this narrative discipline become visible. In a widely used geography textbook published in the twenty first century, the transatlantic slave trade was described as the movement of millions of workers from Africa to plantations. Public backlash forced a revision, but the episode revealed more than an isolated wording error. It exposed how easily coercion is reframed as labor, kidnapping as migration, and theft as contribution when history is edited for comfort rather than accuracy. This was not a relic of the distant past. It occurred within the educational lifetimes of today’s students, demonstrating that the problem is not merely historical amnesia, but an ongoing process of narrative smoothing. Research into educational standards reinforces this conclusion, consistently finding that the ideological foundations of racial hierarchy are often avoided, leaving students with fragments rather than frameworks for understanding the nation’s development. When standards are diluted, textbooks follow. When textbooks follow, a single month is expected to compensate.

What a Once a Year Celebration Does to History

A single annual observance does more than shape classroom schedules. It reshapes incentives for everyone involved in producing historical knowledge. Scholars are encouraged to specialize seasonally. Teachers are asked to compress complex histories into narrow timeframes. Publishers package Black history as supplemental content rather than structural foundation. Woodson anticipated this outcome. In The Mis Education of the Negro, he warned that education could function as indoctrination when it trained people to misrecognize themselves and their society. His concern was not ignorance alone, but a system that quietly normalized inequality by embedding it within the story people were taught to accept as natural. A month is not neutral in that context. It is a mechanism that regulates attention.

The Guest Contract

Over time, Black history came to occupy the position of a guest within the American narrative. It is welcomed, honored, and celebrated, but only within carefully defined boundaries. Guests are not expected to question ownership, rewrite origin stories, or rearrange the structure of the house. They are expected to be appreciative. This unspoken contract explains why celebration is encouraged while authority is resisted. Presence is permitted, but claims to foundational authorship provoke discomfort and backlash. The tension is not about inclusion. It is about ownership of the story itself.

The Global Echo

This architecture did not remain confined to the United States. As American cultural power expanded through media, publishing, and education, the model of a contained month traveled with it. The United Kingdom, Canada, and other Western nations adopted similar commemorative frameworks, often mirroring the same compromise. Black history was acknowledged, but typically siloed, treated as cultural enrichment rather than as a force that reshaped national development. Across the African Diaspora, the American model has been viewed with a mix of gratitude and skepticism, understood as a tactical gain that never matured into structural transformation. The calendar became global, while the deeper question of integration remained unresolved.

The Centennial Question

At the hundred year mark, the debate is no longer whether Black history deserves recognition. The more consequential question is why students can move through most of the academic year studying American history without Black people positioned as central actors in the nation’s development. If the answer is that there is insufficient time, then the system is admitting it allocates time according to value. If the answer is that the subject is too political, then the system is admitting that the default narrative is political as well, only protected. If the answer is that February already exists, then the month is functioning precisely as containment.

The Next Century

A genuine centennial honor for Woodson would not take the form of a larger celebration. It would take the form of redesign. By the middle of the twenty first century, an integrated American history would treat slavery as an economic system directly connected to modern wealth rather than as an isolated moral failure. It would place Black labor, political strategy, cultural innovation, and resistance at the center of national development rather than at its margins. It would present civil rights not as a detour, but as a recurring force that reshapes democracy itself. In such a framework, February would not disappear. It would deepen. It would serve as a moment of synthesis rather than substitution.

The Hundred Year Reckoning

If the first century of Black History began at a wooden desk in 1926, with ink stained fingers working urgently against erasure, then the next century will be judged by what we did with what he left behind. The next hundred years demand a departure from the guest contract that quietly governed the compromise. If 1926 was about getting through the door, 2026 must be about the deed to the house itself. The ink on Woodson’s fingers was never meant to dry inside a single month or remain confined to a special chapter; it was meant to seep into every page until the story could no longer be told without it. One hundred years later, the emergency he sensed has not passed. It has simply been managed. The question before the next century is no longer whether America will listen in February, but whether it is finally prepared to tell the truth for the rest of the year.