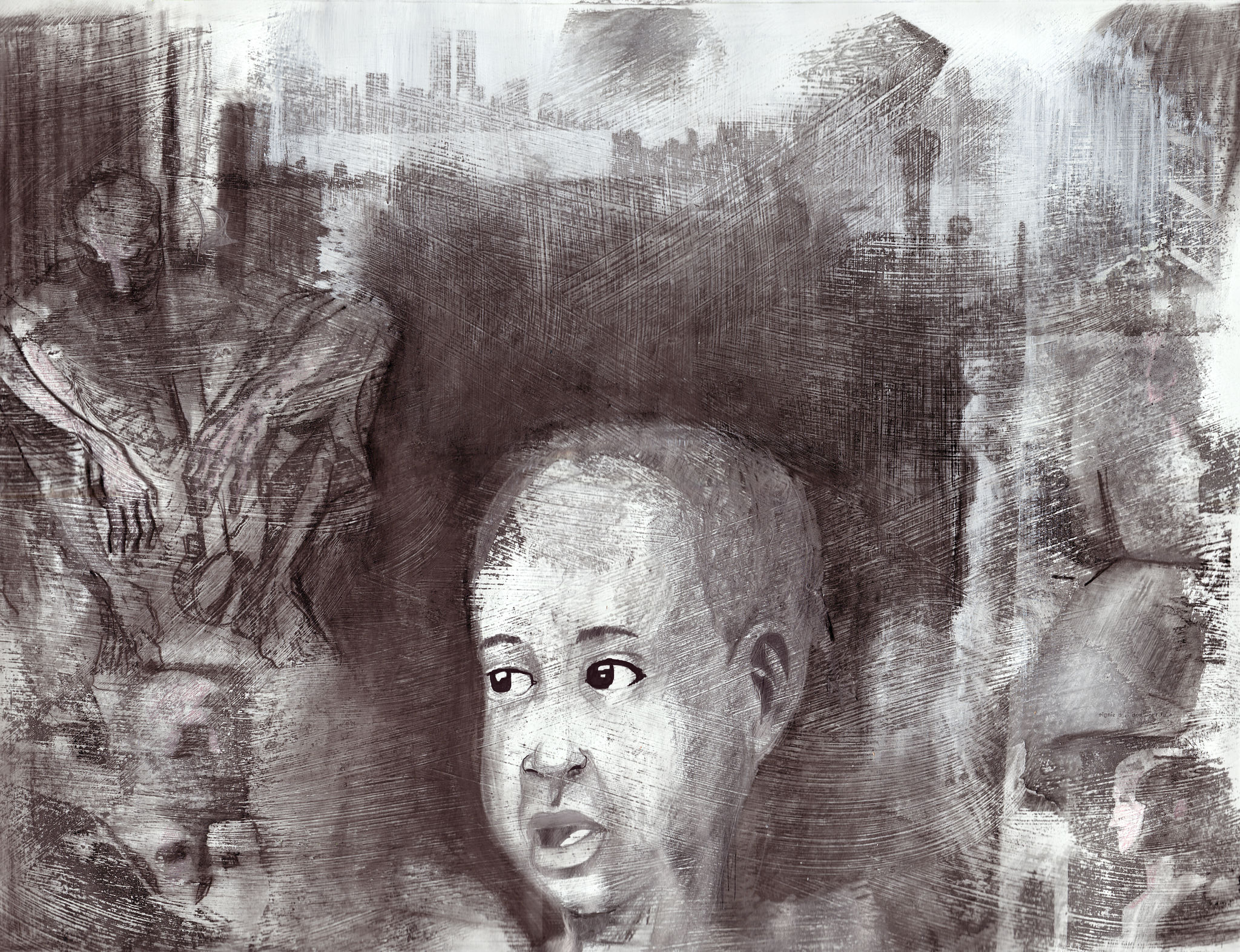

Fair Housing?

The Fair Housing Act and the Hidden Bias in Housing

By Candace Goodman, The Good Blog

As a housing advocate and writer, I’ve seen a troubling truth: more than 50 years after the Fair Housing Act became law, discrimination in housing isn’t just a relic of the past. It’s often quietly woven into everyday decisions, sometimes by people who think they’re being fair. In this post, I want to shine a light on how unconscious biases can still skew housing outcomes—and what that means for families and real estate professionals alike.

Fair Housing Act: A Promise Still Unfulfilled

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was passed to outlaw housing discrimination. It forbids denying someone a home, mortgage, or lease based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. This landmark law—enacted in the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination—promised a new era of equal opportunity in housing. And yet, enforcement of this promise remains a challenge.

Fast forward to today: fair housing agencies are busier than ever. In 2022, there were 33,007 complaints of housing discrimination filed across the country—the highest number ever recorded since data collection began [Housing Discrimination Complaints Reach Highest Levels Ever Recorded, According to Local and National Fair Housing Advocates - Fair Housing Center for Rights and Research] Preliminary data for 2023 shows an even higher total of 34,150 complaints, marking the third year in a row of record-breaking case numbers. It’s a shocking reminder that housing bias is not only unresolved but in some ways intensifying.

What’s driving these complaints? Many involve blatant violations of the law, but experts say a big factor is that bias often flies under the radar until someone speaks up. “Housing discrimination is insidious,” says Lisa Rice of the National Fair Housing Alliance, noting it perpetuates racial gaps in homeownership and wealth. The rising complaint numbers, she and others argue, reflect both ongoing unfair practices and better awareness by consumers. However, they’re also just the tip of the iceberg.

Reported vs. Unreported Discrimination

Those 30,000-plus cases each year are only a fraction of the problem. The National Fair Housing Alliance estimates “millions of instances of housing discrimination occur annually” that never get formally reported. Most people who encounter discrimination don’t realize it or don’t know how to report it. Others fear retaliation or believe nothing will change, so they stay silent. In subtle cases, a family might not even recognize that their rights were violated.

Why is so much discrimination going unreported? One reason is that modern bias is often subtle. Overt racism—an outright refusal to sell or rent to someone because of their race—has given way to softer, harder-to-prove tactics. For example, a landlord or agent might lie and say, “Sorry, that apartment was just rented,” when a Black applicant inquires, even though it’s actually still available. The applicant may walk away unaware they were discriminated against. These quieter forms of bias are harder to catch, but they’re happening every day.

Researchers note that today’s discrimination is frequently “subtle and covert,” unlike the blatant prejudices of the past.

The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets - PMC. In one national study by the Urban Institute, Black and other minority homebuyers were consistently shown fewer homes and offered less help than white homebuyers with identical qualifications. The discrimination isn’t announced; it’s hidden behind smiles and polite excuses. This means many victims never realize they’ve been treated unfairly, which in turn means many violations never get reported.

Housing Discrimination by the Numbers

To understand the scope of the issue, it helps to look at where fair housing violations are being flagged most. Nationwide, the bulk of reported cases involve rental housing, since renting is a common transaction and discrimination (like an unfair denial or restrictive policy) can be easier to spot. Complaints also span home sales, mortgage lending, homeowners insurance, and appraisals. In 2021, over 53% of complaints were based on disability – often things like landlords refusing accessibility accommodations – making it the top category of reported discrimination. But race-based cases were the second most common, accounting for about 19% of complaints. Familial status (for instance, refusing to rent to families with kids) and national origin discrimination were other frequent issues.

Geographically, fair housing complaints come from every part of the country. Some regions, however, see especially high numbers. In 2022, the HUD region covering California, Arizona, and Nevada logged the most complaints of any region, and the Midwest (Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, etc.) wasn’t far behind. Heavily populated states naturally generate more cases, but no state is immune. From big coastal cities to small Midwestern towns, unfair housing practices are being challenged. The persistence of bias is a national problem.

It’s important to remember, however, that statistics only capture known incidents. Fair housing organizations emphasize that many more cases go unfiled. In fact, private fair housing nonprofits handle the majority of complaints that do surface – about 73% of all cases in 2021 – and they assert that far more people suffer in silence. Every number in a report likely represents many more families who didn’t report the landlord who turned them away or the lender who gave them an oddly high interest rate. Housing discrimination has often been likened to an iceberg: the visible tip is supported by a huge hidden mass beneath the surface.

When Unconscious Bias Creeps In: A Hypothetical Scenario

Bias isn’t always obvious—even to the person biased. To see how this plays out, consider a hypothetical scenario that could happen in any real estate office:

A Realtor in a suburban town works with five prospective homebuyers this spring. It’s been a tough market, and four of those five deals fall through. In each of those four failed deals, the buyers’ credit scores turned out too low to secure financing. By coincidence, those four clients were all Black families from the same part of town. The fifth client—who happened to be white—had a strong credit profile and closed on a home successfully. The agent is frustrated; she lost four commissions. Subconsciously, she starts to see a pattern: “Buyers from that Black neighborhood just don’t qualify; maybe they shouldn’t waste my time.”

Now, when a new Black client from that area calls about a home, the Realtor’s mind jumps to that assumption. She finds herself less enthusiastic in helping, perhaps steering the client toward cheaper listings “just to be safe” or double-checking their mortgage pre-approval before investing much time. She might justify this to herself as being efficient or avoiding disappointment. In reality, she’s now unfairly generalizing about clients based on race and geography – a form of discrimination, even if she doesn’t recognize it.

This example shows how an unchecked, unconscious bias can form from personal experience and lead to discriminatory behavior. The Realtor didn’t set out to discriminate; in fact, she prides herself on being fair. Yet, without realizing it, she allowed a string of anecdotes to harden into a stereotype about Black buyers from a certain neighborhood. Psychologists call this pattern confirmation bias – we tend to notice and remember information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs, and we discount or forget information that contradicts them.

In the scenario above, the agent gave extra weight to those four failed deals (which fit a negative stereotype in her mind) and paid less attention to other factors (for example, that plenty of white clients also have credit issues, or that one successful Black buyer shouldn’t be ignored). Over time, her biased belief “felt” true because it kept going unexamined.

There’s also an element of what researchers term illusory correlation – perceiving a link between race and credit trouble that isn’t actually supported by broader data, only by a few memorable cases. Once that illusory pattern takes hold, it can guide behavior in harmful ways. The Realtor’s new client is now being treated with undue skepticism and fewer opportunities because of a stereotype the agent has formed. It’s exactly these kinds of quiet bias-driven actions that the Fair Housing Act was designed to prevent.

The Psychology of Hidden Bias

Modern social science offers insight into why well-meaning people might fall into such traps. Studies have consistently found that implicit biases – subtle, subconscious attitudes – are widespread. In one large-scale test of implicit bias, about 75% of people (across various racial groups) showed a pro-white or anti-black bias on subconscious association tests. In other words, many individuals who would never consciously endorse a racist view still carry automatic stereotypes that can influence their split-second judgments. These biases often operate without conscious awareness, which means a Realtor, lender, or landlord might genuinely think they’re being objective when in fact their hidden prejudices are skewing their decisions.

Crucially, knowing bias is wrong doesn’t make you immune to it. Psychological research by Patricia Devine and colleagues has shown that even people who sincerely believe in equality can still have stereotypes “pop to mind” involuntarily, as a kind of mental reflex. Overcoming that reflex requires active effort. If a housing professional isn’t consciously on guard against bias, they may default to society’s ingrained stereotypes. This is how systemic discrimination perpetuates itself: not through grand conspiracies or explicit bigotry, but through countless small decisions tainted by implicit bias and untested assumptions.

For instance, experiments have demonstrated that people given feedback that confirms a stereotype will learn and reinforce that stereotype far more strongly than if they receive disconfirming evidence. If they receive no clear feedback at all, they often assume their bias was right and even misremember events to fit the stereotype. In housing terms, an agent might have never been explicitly proven wrong in their biased hunches, so those biases persist unchallenged. It’s a psychological reinforcement loop that can only be broken by actively recognizing and correcting one’s own biases – or through interventions like fair housing testing and lawsuits that catch the discrimination from the outside.

Real-World Consequences and Cases

The impact of these biases isn’t just theoretical—it’s visible in housing patterns and verified by investigations. A striking example came from Long Island, New York, in 2019. An explosive three-year undercover testing investigation by Newsday sent out pairs of equally qualified homebuyers, one white and one minority, to meet with real estate agents. The results showed widespread unequal treatment. Black testers experienced discrimination 49% of the time when compared to white buyers with the same qualifications. In other words, nearly half the time, Black buyers were steered away from certain neighborhoods, denied appointments, or otherwise treated less favorably. Hispanic testers also faced disparate treatment in about 39% of tests, and Asian testers in 19%. Many of the real estate agents in the study likely believed they were treating clients fairly – yet the patterns proved otherwise. This kind of systemic bias helps explain why some communities remain so segregated and why people of color often have a harder time securing desirable homes.

Beyond sales, discrimination seeps into other steps of the housing journey. For example, mortgage lending data shows that even when controlling for financial factors, Black borrowers are far more likely to be denied home loans than white borrowers. Recent federal data revealed that roughly 24% of Black mortgage applicants are denied, versus about 10% of white applicants. Lenders often cite credit history as the reason – a factor that itself can reflect past inequalities (such as lower wealth or income due to generations of discrimination). Such disparities illustrate how bias and systemic inequality compound: a biased assumption (like “applicants from that neighborhood are risky”) might lead a loan officer to scrutinize Black applicants more harshly, resulting in more denials, which then feeds the perception that those applicants are less qualified as a group. It’s a vicious cycle.

The ultimate consequence is visible in America’s homeownership gap. As of the end of 2023, only about 45.9% of Black households own their home, compared to 73.5% of white households. This gap has barely budged – in fact, it’s wider today than it was in 1968 when the Fair Housing Act was new. Decades of overt redlining (where banks and governments explicitly marked Black neighborhoods as “hazardous” for loans) created deep inequalities. Those were outlawed, but the unseen biases that replaced them can be almost as destructive. Lower homeownership means less wealth accumulation for minority families over time, contributing to a persistent racial wealth divide. Bias in home appraisals, another current issue, also plays a role – there have been cases where Black homeowners remove family photos and ask a white friend to stand in for them, only to see the appraised value of the home jump dramatically. When stories like that emerge, it’s a glaring sign that stereotypes are still contaminating supposedly objective processes.

Moving Forward: Combating Bias in Housing

So, what can be done to enforce fair housing and root out these biases? Stronger enforcement and education are two pillars of progress. On the enforcement side, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have been stepping up investigations and legal actions. Fair housing organizations continue to conduct testing and bring lawsuits against offenders. The record complaint numbers in recent years are prompting calls for more funding and staff for enforcement agencie. After all, if complaints pour in but agencies lack the resources to pursue them, discrimination will continue unchecked. Some states and cities are also passing their own fair housing laws (expanding protections to LGBTQ+ status, source of income, etc.) and beefing up local enforcement.

Education and awareness, however, are just as crucial—especially for those working in real estate. The real estate industry has begun to reckon with implicit bias in its ranks. For instance, the National Association of Realtors (NAR) now offers an “Implicit Bias Training” course and a video workshop called “Bias Override,” developed with the Perception Institute, to help agents recognize and overcome their unconscious biases.

These programs teach Realtors how stereotypical thinking can “sneak in” and how to consciously interrupt it. Trainees learn to question their gut assumptions – for example, asking themselves, “Am I giving this client the same options and effort I would give someone from a different background?” – and to practice fairness as a skill. While training alone can’t eliminate bias, studies show that when professionals are made aware of their implicit biases, they can take steps to mitigate them in decision-making. In essence, shining a light on one’s hidden prejudices makes it easier to behave in a bias-conscious, fair manner.

Fair housing advocates also stress the importance of accountability. Real estate brokers and managers are encouraged to review how their agents handle clients and to intervene if patterns of bias appear. Government and nonprofit auditors will likely continue and expand paired testing programs to catch discrimination that individuals might miss. And everyday citizens have a role too: learning about fair housing rights and reporting suspicious treatment. If you’re a home seeker who feels you’ve been unfairly denied or steered away, report it – you can file a complaint with a local fair housing agency or HUD. Every report not only addresses that individual situation but helps agencies identify wider patterns of discrimination.

Toward an Equitable Housing Future

Candace Goodman: Writing about these issues, I am reminded that fair housing is not just a legal matter—it’s deeply personal. A home is more than shelter; it’s where we plant roots and build wealth for the next generation. When someone is denied that basic chance because of who they are or what they look like, it’s a personal tragedy and a national injustice. The Fair Housing Act laid the groundwork for justice, but it’s clear that laws alone can’t wash away biases that have built up over centuries.

The challenge now is confronting the bias within. For those of us in real estate, it means taking a hard look at our “gut feelings” and business as usual. Are we giving each client a truly fair shake? Are we sure that a failure or risk we perceive isn’t colored by a stereotype we’ve absorbed? These aren’t easy reflections, but they are necessary. And for communities and policymakers, it means prioritizing fair housing enforcement and outreach so that no one who experiences discrimination goes unheard.

The fact that tens of thousands of Americans still report housing discrimination each year – and likely hundreds of thousands more experience it quietly – should galvanize us. It’s a call to action to do better, from the federal level down to every apartment showing and mortgage meeting. The good news is that bias, once recognized, can be overcome. Studies show minds can be changed and practices improved when we make a conscious effort. If a real estate agent can learn to check their biases at the door, if a landlord can pause and review an application without preconceived notions, if a lender can stick to facts over profiling – then step by step, the promise of fair housing becomes more real.

Half a century ago, America decided that where you live should not depend on the color of your skin, your surname, or any such trait. That principle stands. Now it’s on all of us – neighbors, agents, officials, and readers like you – to uphold it in everyday life. Fair housing is not a one-and-done battle; it’s ongoing. By staying vigilant against our own unconscious biases and insisting on accountability, we can move closer to the day when “objective” truly means objective, and every door in housing is open on equal terms.

Together, we can ensure that home truly is where the fairness is.